One of the side effects of studying science is an appreciation for how insignificant humans are in the scheme of things. It is pounded into your head at every opportunity. We are microscopic compared to the Earth, and Earth is not the center of the solar system. Our solar system is one of billions in our galaxy. Our galaxy is to the universe as grains of sand are to the beach. The universe is unfathomably old, and the Earth has been around for a good chunk of that time but humanity is brand new. In Sagan’s famous cosmic calendar analogy, in which the age of the universe is compressed down to a single year, humans don’t appear until minutes before midnight on December 31. On the scale of the universe in both space and time, humans might as well not exist.

Apart from a thin film of life at the very surface of the Earth, an occasional intrepid spacecraft, and some radio static, our impact on the Universe is nil. It knows nothing of us.

Carl Sagan

This is all true, and it’s important to teach people, especially people who plan to make it their business to study the universe. You need to face reality even when it makes you uncomfortable.

However, it’s a little alarming how gleefully some people like to drive this point home. There’s a sense of smug superiority, a feeling of being somehow above the petty things that concern “ordinary” people. I find this is especially true of certain fields (you get this much more from the physical sciences than biological and social sciences) and certain types of people (especially those who think they have something to prove).

As I have gotten older, I’ve started to realize that despite good intentions, this “minimize humanity” mindset leads to its own flavor of wrong-headed thinking. People begin to mistake feeling smart for being wise.

The test of a first-rate intelligence is the ability to hold two opposed ideas in the mind at the same time, and still retain the ability to function.

F. Scott Fitzgerald

This is one of those cases that Fitzgerald is talking about. Humans are indeed insignificant in both space and time when compared to the universe. But at the same time, we are far more important to each other than the distant reaches of space and time. Both of these things can be true. “Meaning” or “significance” are not laws of physics, they are human constructs. We as humans get to decide what is significant, and the scale of the universe is not the appropriate comparison. Our lives occur on the time scale of decades, and on the spatial scale of a tiny fraction of the surface of the Earth. So what if that’s small compared to the universe? It’s big for us.

Minimizing humanity might help avoid mistakes like saying that the sun goes around the Earth, or that we are at the center of the universe since most galaxies are flying away from ours. But it can also lead to dangerous reasoning like: If humans are insignificant, then how can we be responsible for climate change? Even if you accept that there are enough of us that collectively our actions are significant enough to mess up the planet, it can lead to a nihilistic view that it doesn’t matter. After all, we’re just a flash in the pan. Earth will survive whatever we do. Some species might go extinct with us, but others will adapt and flourish. So who cares? The sun will eventually become a red giant and consume the Earth, and the universe will eventually succumb to entropy. On the scale of the universe nothing matters, everything is insignificant and transient. So if nothing matters why should I care about anyone other than myself and my immediate gratification? A brief bit of hedonism before I return to the nothingness from whence I came.

Of course, that’s a cop out. An avoidance of the uncomfortable responsibility of deciding for ourselves what is meaningful. It’s easier to throw our hands up and say “well, nothing matters.”

LIfe has no meaning a priori. Before you come alive, life is nothing; it’s up to you to give it a meaning, and value is nothing else but the meaning you give.

Jean-Paul Sartre

Man is condemned to be free; because once thrown into the world, he is responsible for everything he does.

Jean-Paul Sartre

This minimization of Earth and of humanity also can trick otherwise smart people into fixating on the wonders of the universe and neglecting the wonders around them. I have been somewhat guilty of this. I was fascinated by science from an early age, and started studying space right when I got to college. I thought I had a pretty good understanding and appreciation for “mundane” stuff and was more interested in the exciting weirdness of the rest of the universe. But of course, I knew almost nothing about life, and now as I get older and have more life experience, I have come full circle: I feel less drawn than I used to be to the mysteries of space which have no bearing on human life, and am more interested in the richness of regular everyday life.

My point is not that we should not marvel at the universe, my point is that, in looking up at the stars we must try not to devalue the wonders that are right in front of us. The things that matter and can bring us real happiness are right here on Earth.

Think of your own life. All the memories and experiences that are stored in your brain. All the relationships, all the places you’ve been, all the things you’ve done. Think of your proudest moments, your greatest disappointments, your loves and your losses. Think of the things you have created, the mark you have made on the world, whatever forms that takes. Just take a moment to recognize the richness of your life and everything you know and have done. These things don’t lose their significance because the universe is vast and ancient. The universe doesn’t get to decide what is significant to you. You do.

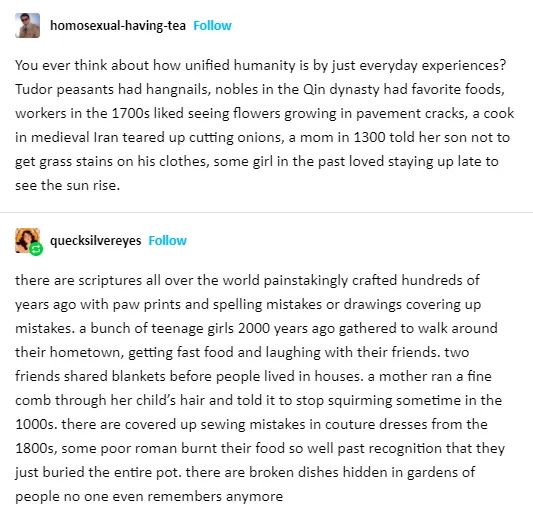

Now consider: there are 7.9 billion other people on this planet. If you looked at one face every second it would take 250 years to look at everyone (and in that time, billions more would be born). Every two years, humanity’s collective experience spans more time than the age of the universe. That’s a lot of people. And what really boggles the mind is that every single one of them has just as rich and vivid and intricate a life as yours. Every one of them has their own favorite places and favorite foods, their own family, their own memories. Every person has things they have created, songs they have sung, dreams they have pursued. Every person has their own story.

Every place and every thing in the world plays a role in countless people’s stories, and has a story of its own. That big tree in the park is just a tree to you, but to someone it’s where they shared a sunny afternoon with their first love. To someone else it is where they were sitting when the doctor called with bad news. To someone else, it’s where they take their family photo every year.

I think about this a lot when traveling or looking at a map: every place that you see is someone’s home. Every house, apartment, street or park, is at the center of someone’s whole life. When you really think about this and stop relegating these things to mere scenery, the world feels anything but small.

It feels even larger when you fold in time as well. Consider not just the significance to people alive today, but the countless lives going back tens of thousands of years. We hear so much about how all of human history is the blink of an eye in geologic or cosmic time, but at the human scale, our history is almost unimaginably deep. We’ve been here long enough for every single patch of the earth’s surface to be rich with human history. Most of it forgotten, but all of it real.

Lately I’ve gotten much more interested in history, especially ancient history and prehistory for this reason. Just as it is eye opening to think of all the places you visit on vacation as someone’s home, it fires my imagination to consider people as real and complex as you and me living thousands or tens of thousands of years ago. Real people peering out over the wilderness of an uninhabited continent, or cautiously trading with tribes of Neanderthals, or waging a forgotten war on the ground we walk every day, or struggling with the timeless day to day tasks of raising a family. I feel the depth of history stretching out into the past, at once unreachable but intimate in our shared humanity.

Yes, we humans are insignificant on a cosmic scale, but so what? We don’t live on that scale, we live on a human scale. Nihilism is a cop-out. We are responsible for deciding what is significant and meaningful, and as anyone who has held a newborn can tell you, it has nothing to do with size or age. You can hold the most important thing in the universe in your arms.

For small creatures such as we, the vastness is only bearable through love.

Carl Sagan