In my previous post I wrote about how the book “Feeling Good” helped clue me in on the major causes of my (mild) mental health issues. It turns out, the need for approval from others and the constant pursuit of external achievements in lieu of real self esteem can lead to anxiety and depression. Right after reading that book, I read a collection of essays, speeches, poetry, and other short writing by Ursula K. Le Guin called “Dancing at the Edge of the World”. Some of the insights in Le Guin’s writing really resonated with what I had just read in Feeling Good, and I’m still thinking about them.

Dancing at the Edge of the World is a strange book, and I wouldn’t recommend reading the whole thing to anyone but the most die-hard Le Guin fan. Some of the essays are brilliant but quite a few are academic and esoteric, and I suspect most of the speeches work better as speeches than on the page. However, despite the challenges, I found it provided the clearest summary I have yet read of the core themes and philosophy underlying Le Guin’s work. In particular, the interconnections between her interest in Taoism, her feminism, her writing, and her general philosophy of life.

As far as I can tell, Le Guin didn’t believe in an afterlife or God or anything supernatural, she just uses Taoism as a way to recognize a dichotomy that pervades much of society between those things traditionally grouped under Taosim’s “Yin” and “Yang”:

| Yin | Yang |

| Dark | Light |

| Passive | Active |

| Moon | Sun |

| Gathering | Hunting |

| Containing | Penetrating |

| Protecting | Attacking |

| Wilderness | Civilization |

| Nature | “Man” |

| Circle | Line |

| Flexible | Rigid |

| Consensus | Authority |

| Decentralized | Centralized |

| Soft | Hard |

| Home | Exploration |

| Repetition | Novelty |

| Stability | Change |

| Female | Male |

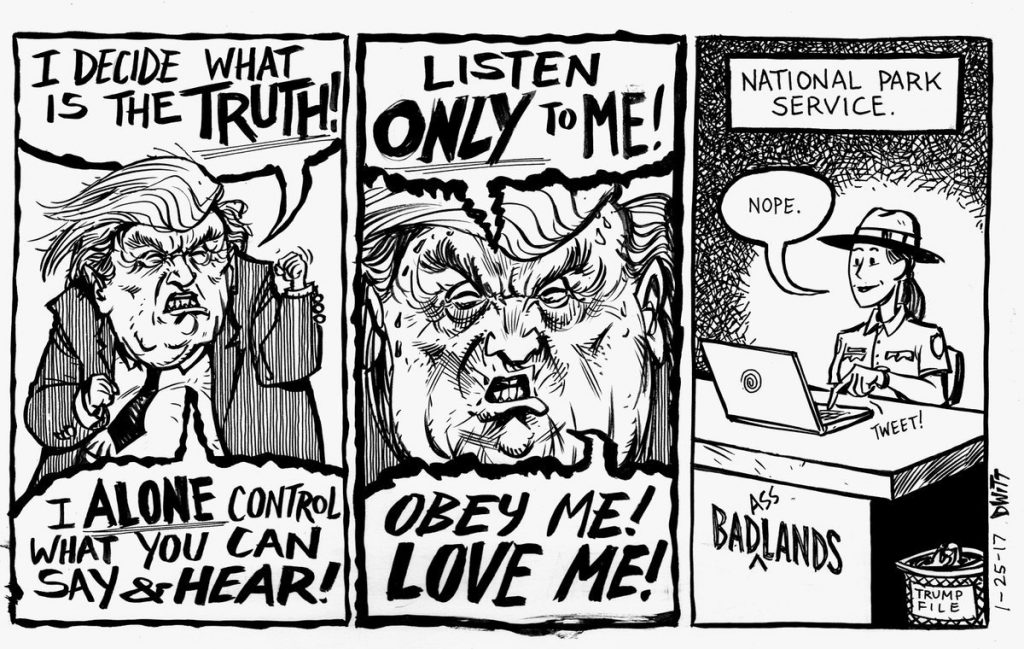

Throughout the essays in the book, Le Guin makes the case that our society is profoundly and deeply biased toward the “yang” or masculine attributes and often downplays the importance of “yin” and those things traditionally considered feminine.

This should come as a surprise to nobody, but the framing in terms of Taoism’s dichotomy was a new spin on it for me. It takes our society’s misogyny and links it up with other biases, some of which are listed above, that may not be as obviously gendered.

She also digs deeper and addresses why there is a pervasive bias in favor of “yang” traits, and proposes that it links back to storytelling. In particular, the following quote from her brilliant essay “The Carrier Bag Theory of Fiction” really resonated with me. In the essay, she discusses the very reasonable theory that, contrary to long-held consensus (among mostly male anthropologists), it is likely that the first tool used by early humans was not the (masculine) spear, but the (feminine) “carrier bag”: Something in which to put gathered food.

It is hard to tell a really gripping tale of how I wrested a wild-oat seed from its husk, and then another, and then another, and then another, and then another, and then I scratched my gnat bites, and Ool said something funny, and we went to the creek and got a drink and watched newts for a while, and then I found another patch of oats…. No, it does not compare, it cannot compete with how I thrust my spear deep into the titanic hairy flank while Oob, impaled on one huge sweeping tusk, writhed screaming, and blood spouted everywhere in crimson torrents, and Boob was crushed to jelly when the mammoth fell on him as I shot my unerring arrow straight through eye to brain.

That story not only has Action, it has a Hero. Heroes are powerful. Before you know it, the men and women in the wild-oat patch and their kids and the skills of the makers and the thoughts of the thoughtful and the songs of the singers are all part of it, have all been pressed into service in the tale of the Hero. But it isn’t their story. It’s his.

Ursula K. Le Guin

Humans are storytellers, and so we are biased toward the sorts of actions that make for an exciting story. Things with danger, adventure, change, and heroes. And when all of those story-worthy things are culturally defined as the domain of men, it’s no wonder that the result is a bias in favor of men and anything seen as masculine, and against women and anything seen as feminine.

LeGuin goes on to highlight how this bias toward the “masculine” is pervasive in science fiction, choosing in particular to pick on Arthur C. Clarke’s 2001: A Space Odyssey:

Where is that wonderful, big, long, hard thing, a bone, I believe, that the Ape Man first bashed somebody with in the movie and then, grunting with ecstasy at having achieved the first proper murder, flung up into the sky, and whirling there it became a space ship thrusting its way into the cosmos to fertilize it and produce at the end of the movie a lovely fetus, a boy of course, drifting around the Milky Way without (oddly enough) any womb, any matrix at all? I don’t know. I don’t even care. I’m not telling that story.

Ursula K. Le Guin

I highlight these two quotes not just to convince you that you should go read everything by Le Guin (though you should) but because they were particularly resonant for me given the circumstances in which I read this particular Le Guin book. I was on paternity leave, taking time off of work to take care of my growing family and was feeling anxious about it. Why was I feeling anxious? As I discussed in my previous post, taking a lot of paternity leave is not as widespread as it could/should be in my workaholic field (or in American society in general), and I had some level of irrational paranoia that people would disapprove of how much leave I was taking.

The Le Guin essay helped to get at a reason for this paranoia: taking paternity leave is an act that, at least temporarily, prioritizes traditionally feminine roles (caring for family, staying at home, domestic life) over the more “masculine” roles (being the primary earner, going to work, prioritizing career, etc.) that I have been taught that people expect from me, even if I would prefer something more balanced. And as Feeling Good taught me, I’m overly susceptible to letting my mood get wrapped up in speculations about what people think of me.

It’s not just paternity leave; Le Guin’s framing of our cultural misogyny in terms of bias toward “heroic” or “yin” or “masculine” traits resonates in other ways.

In the section of Feeling Good that tries to help the reader overcome the obsession with achievement, there is a fictional dialogue that pits a chronic overachiever against their former high school classmate who is happier and less addicted to achievement. The overachiever went to a prestigious school, got a PhD and has a lucrative, jet-setting, influential job. The more well-adjusted person is a high school teacher and coach with a family and a happy, more locally-oriented life. The point of the dialog is to take the idea that achievement (traditionally defined) makes a person more worthwhile to its ugly logical conclusion to show just how absurd it is, so the overachiever comes across as a completely unreasonable jerk.

Unfortunately, although it’s not a perfect match, I do see some of myself in that jerk. Even though the overachiever in the dialog is supposed to (and does) come across as an awful and unpleasant person, I’m ashamed to admit that there is a part of me that still thinks they have a bit of a point. It whispers in the back of my mind that, really, if you think about it, your life is more worthwhile if you are famous and influential and achieve things that will last long after you’re gone.

And this brings us back to the bias not just toward masculine traits, but “heroic” traits. A hero is someone who is famous and influential, whose actions changed the world, about whom stories are told. In short, a hero achieves a sort of immortality. Conscious or not, I think that taste of immortality is why our society has a bias in favor of these traits.

(I feel like I’m lacking the appropriate words here. “Heroic” has positive connotations, but what I want is a word that means roughly the same thing but is more neutral, because my whole point here is that equating “heroic” traits with positive, and therefore implicitly saying that “non-heroic” traits are negative, is a big part of the problem. Since language is failing me, I’m going to keep using “heroic” as shorthand. So, just pretend I have found a less-loaded version of the word and am using that instead.)

Humans learn by telling stories, and almost every story that we tell reinforces this bias, to the point that it becomes a real challenge to conceive of stories that really center on the “yin” attributes. Le Guin talks about this challenge, and I think her conscious effort not to tell variations of the same old heroic, masculine story, while still working in the fantasy and sci-fi genres that are so dominated by that story, is a large part of what makes her stories so refreshing and distinctive and interesting. (It helps that she’s a good enough writer to pull it off…)

Alas, not all authors are Ursula K LeGuin, so we exist in a culture that is steeped in stories that almost all reinforce the same traits. Reflecting on myself, and my own motivations, it’s hard to deny the influence, and it is also hard to deny that a lot of the angst I’ve been working through in the last few years has been a process of breaking through those patterns of thoughts and values and acknowledging that I am in a stage of life where, essentially, my focus is shifting from “yang” to “yin” and that that’s okay.

Though I don’t love to admit it, part of my desire to become a scientist was the alluring myth of the “great scientist” whose amazing contributions to science not only advance our understanding of the universe, but also earn a place in the Pantheon of great scientists. Of course in reality, science is a collaborative effort where most big discoveries are made by teams, but that doesn’t fit the narrative. That doesn’t provide the story with a singular hero.

Not only is science a team effort, I have also discovered that I don’t really like being the leader of the team. I’m much more comfortable and effective in a supporting role. For example, my work to improve the accuracy of ChemCam’s measurements feeds into almost every paper and discovery the team has made. The cumulative impact is almost certainly greater than if I had focused my efforts on leading a few scientific papers. And yet it has been really difficult to come to terms with the idea that I prefer doing “behind the scenes” work. I feel guilty that I am not writing amazing papers that end up getting all the attention of other scientists and the press. There’s a part of me that is still the anxious grad student, irrationally worried about what my advisor would think of my path and my preference for the less flashy work (there’s that approval seeking again). I hate that I feel a pang of jealousy when friends publish big, attention-grabbing papers. A part of me feels like a failure for not living up to the “great scientist”myth. The bias toward “heroic” or “yang” traits, toward constant striving for the next big achievement, is strong.

It shows up in my goals for the future as well. I’m not content to just want to be a good science communicator, there’s a part of me that will see it as a failure to be anything less than the next Carl Sagan. I’m not content to just try to write a book, I’ll be a failure unless I am the next George R.R. Martin. Of course, this part of me is almost entirely counterproductive. It has not spurred me to make great strides in either of these areas, it just needles me enough to attempt things and then abandon them as I stress out about the impossible expectations I impose on myself. It maintains a constant cycle of anxiety and disappointment in myself, but never gets channeled into a truly motivating force for long enough to break free and rise to the level of something positive like inspiration. My hard drive is littered with fiction and nonfiction writing projects abandoned in the first chapter. Heck, even this blog has a good number of aborted posts in varying states of completion, in large part because of the unrealistic expectations I set, and the paranoia about what people will think. (This blog post came perilously close to being one of them.)

The good thing is that with the perspectives afforded by Feeling Good, Dancing at the Edge of the World, and more generally the realignment of priorities that comes with maturing and having kids, I am gradually starting to move toward a more balanced attitude.

A good example of this is how I feel about being an astronaut and human space exploration in general. In college when people asked me if I would go to Mars if I was given the chance, I said yes with minimal hesitation. I even considered applying to be an astronaut a few times. But as I have gotten older and built a family and a life and grown to appreciate the Earth, my answer has changed. The temptation is still present – the bias is strong – but it’s no longer an easy decision. I have a lot more to lose. My default answer would now be “no” and it would take convincing and a lot of caveats and guarantees to change that to a “yes”.

A corollary to that is how my attitudes toward building a Mars base have changed. For a long time I was strongly in favor of it, both scientifically and as an “insurance policy” in case of a global catastrophe here on Earth. Now I see the idea of Mars as a “lifeboat” for Earth as deeply flawed and problematic. It provides a comforting fantasy as if it is a valid option, and people cling to it rather than facing the more important but more difficult challenge of changing our society so that we become good stewards of the wonderful planet we live on. People gravitate toward the “yang” option (exploration, colonization, risk, heroism) and shun the “yin” option (staying where we are, taking care of our home). We’re sitting here destroying the literal paradise that is Earth and saying, “Don’t worry, the billionaires will save us. With their rockets we could maybe eke out a miserable, dark, cold, dusty, claustrophobic existence in underground shelters on Mars,” as if that’s a solution.

Anyway. I’m getting off track. The point is, my perspective on things is changing, and one way to frame that change is as a shift from thinking that is strongly biased toward the “heroic”/”masculine”/”yang” traits to an attitude that is hopefully more balanced. I don’t need to be the great scientist, I am happy to support others. I don’t want to colonize a new world as much as I want to take care of our home. I am not that interested in jet-setting around the world, I’d rather stay home and enjoy time with my family.

A major theme in this shift of perspective can be summed up as coming to peace with the idea that I am not exceptional, and that is ok. To be clear, I’ve never had the kind of self esteem that allowed me to go through life thinking “I’m exceptional.” But despite that, I have spent a lot of angst convincing myself that I need to make a mark of the world so that when I’m gone there will be some evidence that I lived. It’s that lure of the immortality of the “hero.”

I’ve achieved some things that I’m proud of and my name is on a number of scientific papers that will hopefully be read for a long time into the future. Or if not read (let’s be realistic), then at least they’ll exist. There will be evidence in the world that I existed and did a certain type of science. But when push comes to shove, I’m a pretty boring, normal, privileged white dude. My life is mostly like the life of millions of others. When I am gone, my friends and family will miss me, but then they will go on with their lives and that will be it.

There’s a flaw in the sort of thinking that says that you’ve only left your mark on the world if people remember you, or if you did something that has your name on it. That’s a very “hero-biased” way of looking at things. Sure, writing the great American novel or making a major scientific discovery or walking on Mars or becoming president or any number of other ways to be famous and influential can guarantee that you’ve left some sort of mark, but that’s not the only way.

The truth is that we are all constantly making our marks on the world, whether we, or others, recognize it. We should think of our influence not as a discrete achievement or event that plants a flag and announces “here is my legacy” but more like concentric ripples, expanding away from ourselves into the world as we move through our lives. Everything we do has an influence, and the world is too large and chaotic to know when any given action or choice will go on to have a profound effect and when it will amount no effect at all. All we can do is try to make good choices, be generous with our time and our resources and ourselves, and try to leave the world better than we found it.

I’m not saying that we should not pursue big goals, nor am I implying that simply being a good person is sufficient to effect positive change in the world. I’m saying that the amount of recognition that we receive for the things we do has little to do with the significance of the legacy we leave when we are gone. I can work hard and get recognition for achieving major goals like publishing scientific papers and writing books, but it’s entirely possible (and perhaps more likely) that the greatest impact I’ll have on the world is through things that get much less recognition like raising my kids, donating to good causes, and doing political volunteer work.

More important than recognizing that I don’t have to do things that get recognized by others to leave the world a better place is the recognition that no matter what I do, big or small, my legacy will be ephemeral. Here I’ll bring in another book I recently read: Conqueror, by Conn Iggulden. It’s the 5th book in a historical fiction series about Genghis Khan and his successors. I was not expecting to find insight into the topics of this essay in a book about Mongol warlords, but books can be surprising that way. Conqueror focuses on Kublai Khan’s rise to power, and the final lines of the book are Kublai talking to his son:

“I would like to change the world,” he said.

Kublai smiled, with just an edge of sadness in his eyes.

“You will, my son, you will. But no one can change it forever.”

Conqueror, Conn Iggulden

Maybe part of this process that I’ve been going through, this shift in perspective, is a growing acceptance of the fact that life is ephemeral and a realization that trying to deny that fact is the recipe for a lot of pointless angst. Taken the wrong way this could be seen as nihilistic and depressing, but it’s actually kind of liberating.

I have been trying to pay attention to what actually makes me happy and here’s what I found: happiness comes from the ephemeral, from living in the moment, from being so caught up in the present, in the sensations, the feelings, the task at hand, that self-consciousness falls away. You can’t think your way to happiness. You can’t set it as a goal to achieve.

This is not a particularly new insight. None of this post is, really. But it’s one thing to hear some of these things in the form of quotes and platitudes and another to really internalize them. To use a physics analogy, it’s the difference between being given the equation and deriving the equation from first principles.

Looking back over this post, I worry that it comes across as implying that “masculine”/”yang” traits are toxic and “feminine”/”yin” traits are good. That’s not my intent. It’s good to have goals, to try to achieve great things. But the point is that our culture, our stories, my educational background, my professional life, all have a strong bias toward the “yang.” Toward constantly striving to live up to the “heroic” ideals. This often leads to neglecting the richness of the “yin” side of life, which is a recipe for the anxiety and depression that I’ve been struggling with.

I’ll end with one more relevant quote from a book I recently read. This time from “A Little Life” which is one of the best books I’ve ever read but is also devastatingly sad. It deals with what makes life worth living even in the face of horrible suffering, and at one point the main character thinks:

It had always seemed to him a very plush kind of problem, a privilege, really, to consider whether life was meaningful or not.

Hanya Yanagihara, A Little Life

This quote puts its finger on one of the reasons I feel uncomfortable about these long, over-earnest, self-indulgent, pseudo-philosophical blog posts. I have a wonderful life, and it is because I don’t have to do things like work three jobs or worry about whether my family is safe that I have the luxury of analyzing all the reasons why I sometimes feel anxious for no good reason. It makes these blog posts feel embarrassing and faintly obscene even though (or perhaps because) they do capture and help me process the thoughts that rattle around in my head. So, just for the record, I understand that posts like this warrant at least some eye rolling, especially from people with real problems.

If you’ve made it this far, thank you for letting me indulge in this privileged rambling. This post in particular was difficult to write. It ended up far longer, and took far longer to write, than expected. It makes me uncomfortable to post this, but that discomfort probably means I’ve hit upon some important themes that are worth posting. Bottom line, here are my take-away lessons:

- My life is shifting from a focus on achievement and a general bias toward “yang”/”heroic” type traits to a focus on home and family and a greater emphasis on the “yin” side of things.

- Despite deeply ingrained biases in culture, stories, professional settings, etc., the shift toward a more balanced life is not only okay, it’s healthy and good.

- That said, some of my anxiety comes from the conflict between that cultural bias and my shifting priorities.

- Stressing out about leaving a legacy through my actions is just a recipe for anxiety. Life and everything in it is ephemeral, and fighting against that truth is a losing battle. Better to focus on living in the moment, accept what is happening in that moment without judgement, and do things because I enjoy the process rather than to achieve some lofty goal.