What is the purpose of a gun?

It’s a question I’ve been thinking about a lot since the Las Vegas massacre, and has come to the fore again with the massacre in Parkland and the national discussion about gun violence that has followed. It’s a simple question, but it’s one that I think doesn’t get enough attention, because the answers get to the heart of the gun debate in the United States.

The simple answer to this question is that a gun is a device for propelling projectiles at high enough velocities to kill animals at a distance. More specifically, many guns are for killing human beings. That’s what guns are designed to do. But when I ask about the purpose of a gun, I don’t mean “what do they literally do?” I mean, “why do people buy them? Why do people think they need guns?”

Many gun owners will say that they own guns for defense. They want to protect their property, themselves, and their families from harm. Others will say that they own guns for hunting: killing animals for sport and/or food, and all of the culture and traditions that go with that. Polls show that those are far and away the two main reasons people own guns. Of course, guns serve another purpose as well: they are used in war for killing people. Our species has put a lot of effort into finding better ways to kill each other, and modern firearms are one result.

So, guns are for self defense, hunting, and war. But guns are more than just simple tools. Guns have a deep cultural significance that other tools don’t. People get emotional about guns. Why is that?

It helps to look at those three purposes more closely. Self defense, hunting, and war are intimately linked with our culture’s ideas of masculinity. The “man of the house” is traditionally responsible for keeping his wife and kids safe. Hunting is a manly thing to do: it is a rite of passage for boys to go out hunting with their fathers, and bringing home meat to feed the family again plays into the idea of the man’s role as provider for the household. And soldiers are seen as the epitome of masculinity, taking the man’s role of defender of the family and expanding to to defender of the country. Historically, killing has been a man’s job.

The purpose of a gun in modern American culture is not just as a tool, but as a talisman of masculinity. A fetish, worshiped for its power to confer masculinity on its wielder.

Couple the gun’s near-mystical status with a culture that is deeply misogynistic, where men seek to distance themselves from anything that seems even remotely feminine. The easiest way to insult a man in our culture is to question his masculinity, to imply that he is in some way woman-like. Men are taught that they must constantly prove their masculinity to themselves and each other, so what better way than to acquire guns? Surely nobody can question my masculinity if I own an arsenal of military-grade weapons.

At the same time, expressing any emotion other than anger is seen as feminine and therefore forbidden to any self-respecting red-blooded man. Boys don’t cry. Boys are supposed to like gym class and play sports so they can prove their physical prowess against other boys. Boys are not supposed to like poetry or drama, because those activities involve openly sharing emotions other than anger.

That said, our culture is changing fast. Women are breaking down barriers everywhere you look. Same sex couples can get married. Nerds are cool. The #MeToo movement is exposing rampant sexual harassment and men who have long gotten away with it are finally facing consequences. We had 8 years with an African American president. Cherished bastions of popular culture like Star Wars and superhero movies are having success after success by featuring women and people of color.

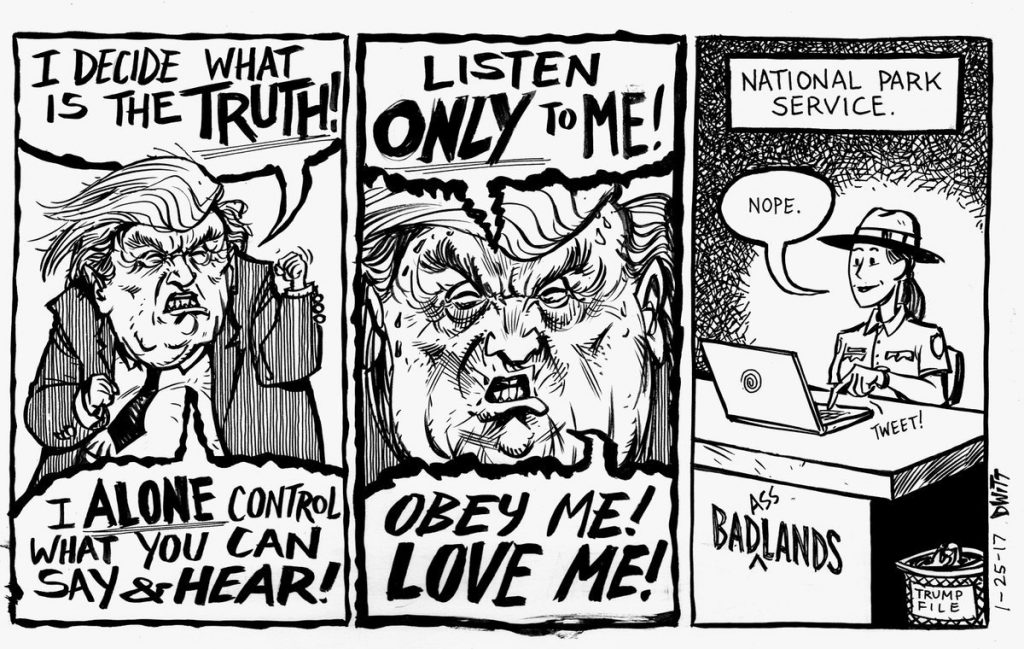

There’s a saying that goes: “When you are accustomed to privilege, equality feels like oppression.” Right now a lot of white men, raised in a hyper-masculine culture, are seeing these shifts and feel like they are under attack. Plenty of men are able to adapt to the changing culture and celebrate it, but there is a segment of the population who instead double down on toxic masculinity. They perceive a threat to their way of life, and in response they acquire arsenals and continue to repress emotions to prove their masculinity at any cost.

There is another facet to guns that also comes into play here. Not only are they powerful symbols of masculinity, but guns offer the illusion of control. It is terrifying to think of an armed intruder breaking into your house and threatening your family, so many people want a gun so that if such a situation arises, they will not feel helpless. They can take control of the situation rather than wait for the cops to arrive. Studies show that having a gun in your house actually puts your family at greater risk, but it feels like it does the exact opposite. Likewise, the idea of a mass shooting is terrifying, and makes people feel helpless. You hear gun advocates say that they want to carry weapons to prevent such attacks, that if we just had more “good guys with guns” then we’d be safer. What they are really saying is that they cannot deal with feeling helpless if such a situation were to arise. By carrying a gun, they feel like if they found themselves in an attack, they could do something about it. This is of course not backed up by reality, where having numerous armed civilians in a shooting is likely to just add to the chaos, cause additional unwanted injuries, and make it much harder for law enforcement to do their jobs effectively. But the idea of having a gun is comforting because it gives an illusion of control.

So what we end up with are heavily armed, emotionally stunted, white men who feel like their way of life is under attack, and turn to guns as a way to reassert control. It’s the perfect recipe for gun massacres.

It is obvious that this country needs better laws to make it harder for dangerous people to get their hands on weapons that make killing easy. But I think it is equally obvious that gun violence in this country is also a byproduct of a deeply toxic culture of masculinity, and that if we want to curb the violence we need to work hard to change that culture.