On May 10, 2024, I am having surgery to remove my gallbladder.

It has been a long road of figuring out symptoms, trying to rule out other causes, learning, and indecision. Writing this all out is a way for me to process everything, to tell friends and family what’s going on, and hopefully provide useful information for others out there who may be in a similar situation. This is going to be long, but hopefully interesting and useful to someone.

Before we get any farther: heads up that this post will include frank discussion of digestive symptoms, medical conditions, and generally gross body stuff that some may consider to be Too Much Information. I’ll try to keep it relatively tame, but if you don’t want to read about this sort of thing, stop now!

History and Symptoms

I would start at the beginning, but it’s unclear when exactly that was. For many years I have occasionally suffered from very painful digestive symptoms. The first of these “attacks” that I remember occurred on November 6, 2012. I recall the exact date because it was election day. I was driving back to Arizona from California where I had been doing operations for the Curiosity Mars rover. It’s a long drive, so I spent the day sedentary in the car and eating fast food. That evening at home, as election results were coming, I was lying on the floor suffering from what I thought was a painful bout of gas.

Over the years this would happen occasionally with varying severity, and each time I just figured it was bad gas. I usually could (and did, and do!) eat whatever fatty food I wanted, but sometimes when I ate a large/heavy meal, especially if that meal also included a few alcoholic drinks, and especially if I was mostly inactive that day, I would end up triggering what I now know was a form of gallbladder attack.

Part of why it took so long to figure out what was happening is that my pain is usually not easy to localize. Often gallbladder attacks are described as a sharp stabbing pain in the upper right abdomen right where the gallbladder is. For me, it starts with “epigastric” cramping across the front of my abdomen, under the ribcage. As the intensity ramps up, the pain spreads to the upper middle of my back, like the muscles between my shoulder blades are extremely tense but no amount of stretching or rubbing can relax them. Often, it’s the inexplicable upper back tenseness that really clues me in that an attack is coming. There’s an irresistible urge to move, walk, stretch, anything to find a comfortable position, but there is no comfortable position. At the peak of an attack, I’m rolling on the floor, sweating, shaking, and generally miserable. During my worst attacks, my hands and arms went all tingly. The only things that slightly help are walking and a hot shower or bath. And to further confuse things, the attacks don’t just feel like gas, they are accompanied by gas and bloating. They tend to occur in the evening and last most of the night (one memorable attack had me awake and wandering the neighborhood moaning in pain like some deranged zombie all night on Christmas eve), subsiding in the morning. After an attack, it tends to take a day or so for my digestion to normalize. It’s almost like whatever happens completely shuts down my digestive tract and it needs time to reset and start working again.

A few years ago the symptoms were happening often enough that I changed my diet, cutting out all alcohol for several months, and switching from bagels and cream cheese to raisin bran for breakfast. This seemed to help, and even now that I do drink alcohol again, I usually only have problems once or twice a year.

In the last couple of years, I’ve also started to have symptoms of reflux. Often not traditional heartburn, but when my stomach is full and I do something like a plank or bend over or exert myself I can feel my stomach contents “overflow” and start moving up my esophagus. Rarely, after a really big meal, I’ll sometimes wake up at night on the verge of vomiting, but without nausea. Just… overflowing. (I know, it’s weird and gross) For a long time I’ve also often had to clear my throat a lot after eating (my dad does this too, so it’s likely some combination of our particular biology and learned behavior). Recently I’ve noticed that I need to do it more and that I’m increasingly prone to losing my voice if I talk a lot. Altogether, my reflux symptoms are most consistent with something called “silent reflux” or laryngopharyngeal reflux (LPR).

It’s unclear if this reflux stuff is related to my gallbladder issues or not but I’m quite curious to see if it changes after surgery.

Doctors and Tests

For a long time, I didn’t really go to the doctor, ever. I was young and healthy and didn’t see the need. But I’m almost 40 now, so last year I finally set up an appointment to establish care with a general practitioner. At the appointment, as I discussed my health history with my doctor, I mentioned these rare but severe bouts of pain. I said that I was pretty sure they were just gas, but figured it was worth mentioning. He ordered blood work and an abdominal ultrasound just to be safe.

At my follow up appointment with him after the ultrasound, he said (I didn’t actually get to see the images at this appointment) that it had come back showing “gallstones” and that he had referred me to a surgeon. This was shocking to me and seemed awfully drastic for something that only occasionally bothered me, so I told him I’d like to wait and see. (He also apparently had sent me a message that I missed about the gallstones and surgeon referral, so at the actual appointment I learned of all this from a casual remark along the lines of “So, you saw my message about the gallstones and the need for surgery…”) He agreed with holding off on surgery but recommended that I talk to a gastroenterologist about both the gallstones/abdominal pain and the reflux.

At the gastroenterologist, they listened to me describe my attacks, and said that it sounded consistent with gallbladder issues. (I have since learned that a whole host of GI symptoms can end up being gallbladder related.) They ordered two additional imaging tests to figure out what might be going on. The first is called a hepatobiliary iminodiacetic acid (HIDA) scan, and the second was an upper GI x-ray series with air contrast. I’ll describe the HIDA scan below, but first let’s review some basics.

What is a gallbladder? What is a gallstone?

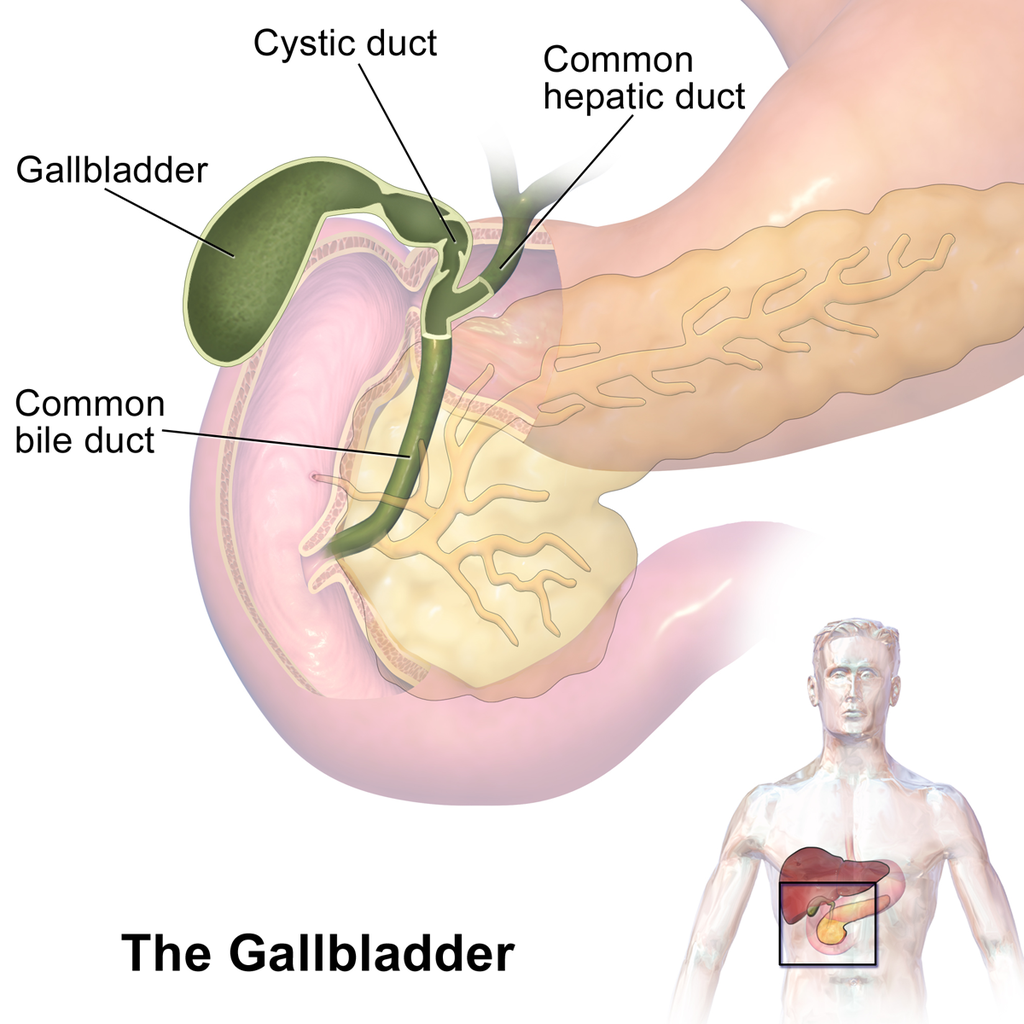

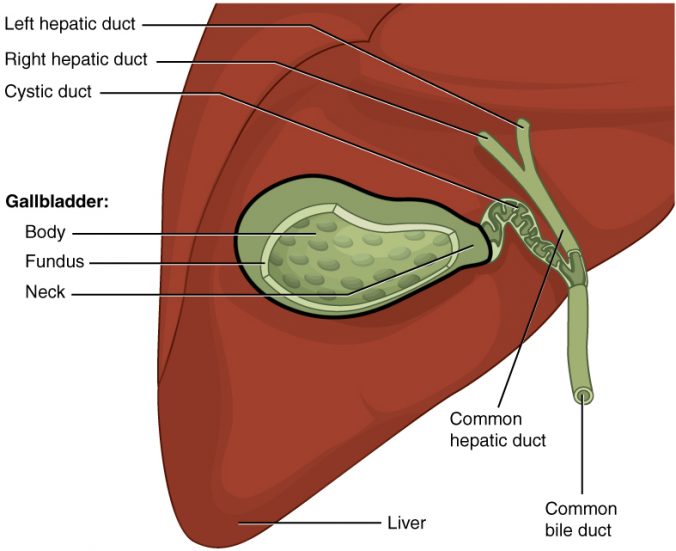

The gallbladder is a small organ that sits just below the liver, in the upper right part of the abdomen. It’s a small sac (normally about 4 cm by 10 cm when full) that acts as a reservoir for bile, the chemical produced by the liver that helps break down fats in your food. When you eat a fatty meal, as that fat enters the upper portion of your intestines (the duodenum), it triggers the release of a hormone called cholecystokinin (CCK). CCK tells your gallbladder to contract, releasing bile through the bile duct into your duodenum to break down the fat.

Most gallstones form when the bile in your gallbladder contains too much cholesterol (which can occur for various reasons) and it essentially crystalizes and precipitates out as a solid. Some gallstones are “pigment stones” and are formed from bilirubin and salts that occur in bile. These are less common than cholesterol stones.

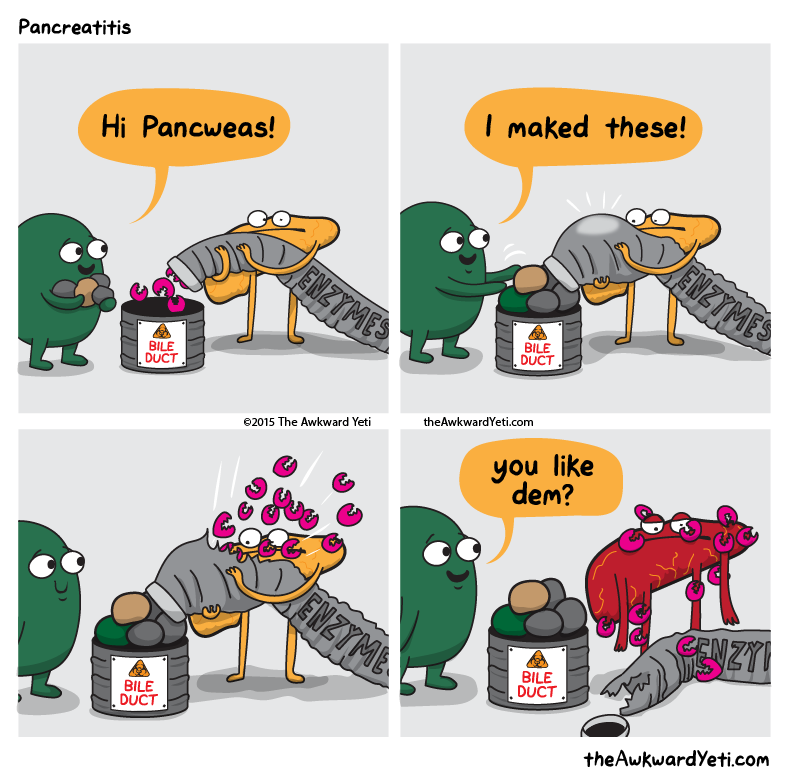

Gallstones cause problems because they block the bile duct, so when your body tells the gallbladder to contract, it does, but nothing happens. So it tries harder, and harder, essentially going into a self-destructive muscle spasm, and then you’re in excruciating pain. Small stones can actually get lodged in the bile duct, or even end up blocking the liver or pancreas which is a life-threatening emergency. Likewise, the gallbladder can become necrotic or burst, which is also life-threatening.

Larger stones are too big to fit through the bile duct (which is normally pretty tiny, just a few mm), so in some ways are safer than small stones, but can cause chronic inflammation of the gallbladder that can lead to significantly increased risk of gallbladder cancer, especially for stones larger than 3 cm.

Usually, gallstones are diagnosed via ultrasound. They can also show up in x-rays and MRIs. Many people have gallstones that don’t cause any problems at all, but once they start to cause problems, the problems generally don’t go away.

What is a HIDA Scan?

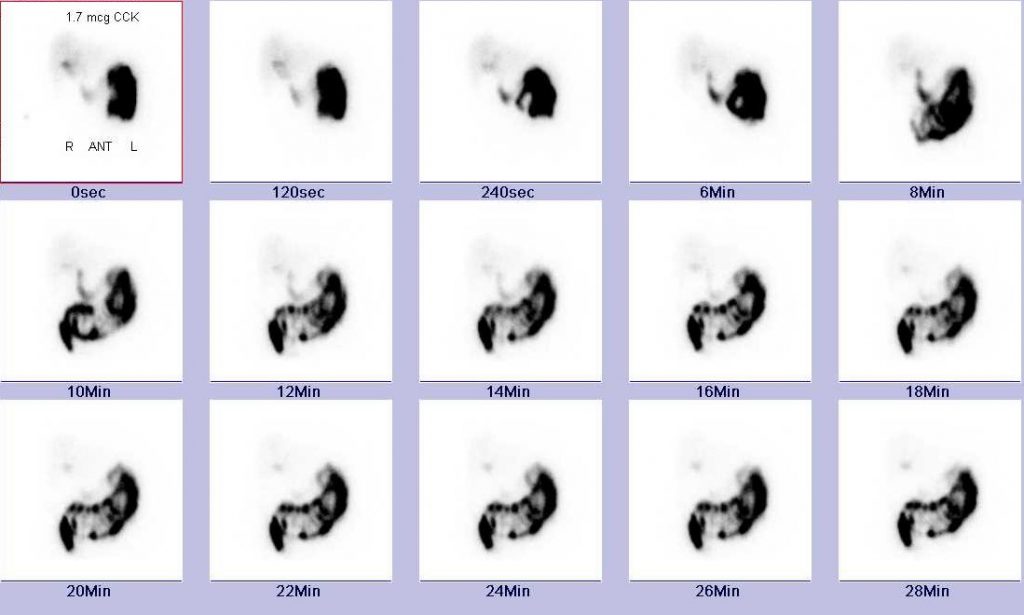

A HIDA scan is a test that lets doctors see how well your gallbladder is functioning. It uses a radioactive tracer (technetium-99) that is injected into your bloodstream. The tracer is incorporated into a chemical that is processed by the liver and passed into the gallbladder in bile. The tracer emits a small amount of gamma rays that easily pass through the body and can be detected and turned into an image of your gallbladder.

Before the scan I was told not to eat anything so that my gallbladder would be full of bile. The scan usually has two parts. First, they inject the tracer and you lie still on the scanner (basically a firm bed with a large boxy device above your abdomen) for about an hour. This lets the tracer get passed from your blood, through the liver, into the gallbladder.

Next, you are given something to trigger the gallbladder to contract. For me, they used an injection of CCK. I’ve also heard of some places that just have you drink a fatty drink like Ensure.

Triggering the gallbladder can cause an attack, especially if you have a stone blocking the bile duct. I was worried I would be in excruciating pain, but for me it wasn’t as bad as a real attack. I felt a sort of fluttering feeling as the gallbladder contracted, followed by nausea and tightness and discomfort similar to my attacks but maybe 10% as bad. This lasted for about 10 minutes and then subsided.

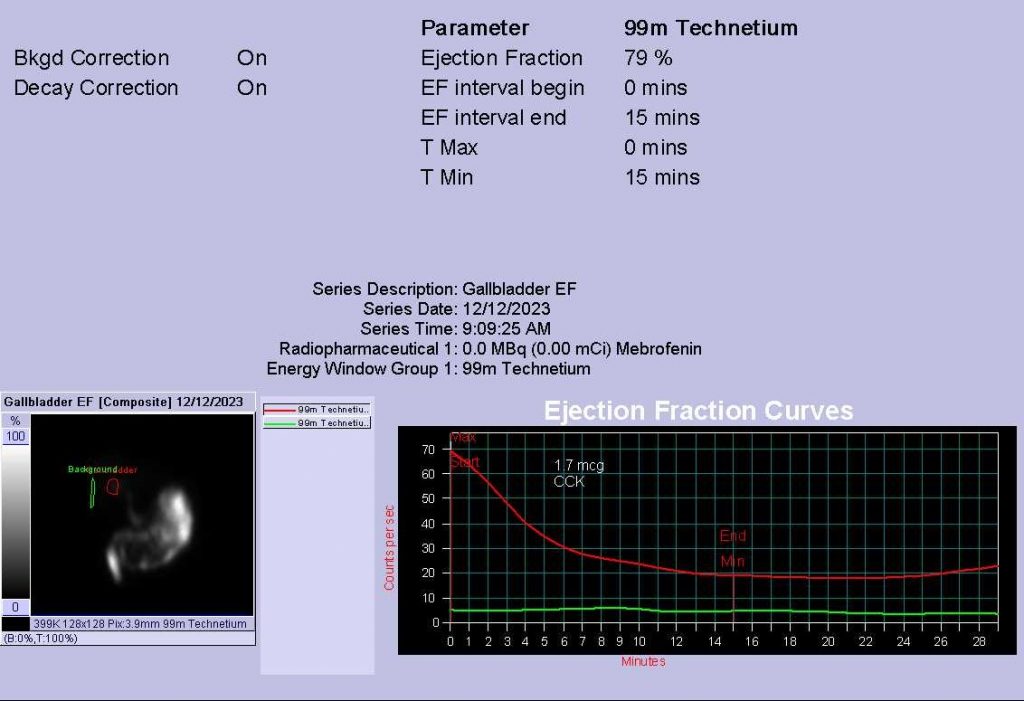

By measuring how much signal is coming from the gallbladder before and after triggering it to contract, the radiology technician calculates the Ejection Fraction (EF). Basically, how much of the bile in your gallbladder gets squirted out when it is told to do its job. Generally an EF of less than 35% is considered low, and can be reason to have surgery even in the absence of stones.

Recent research is also starting to suggest that an EF that is too high (“hyperkinetic”) can cause problems. Basically, your gallbladder overreacts and spasms when stimulated, dumping too much bile and causing pain and inflammation along with other digestive issues. The threshold for what is considered “too high” an EF is not well defined, but generally around 80%.

One thing I learned in reading about it is that there’s a pretty large uncertainty in the EF measurement. Many people get hung up on the precise number but often the more important thing is not what the EF number was, but whether the scan replicates your symptoms. If you have issues when your gallbladder is stimulated to contract during the test, it stands to reason that your gallbladder is likely the problem.

What nobody told me was that the gallbladder activity triggered by the HIDA scan can cause digestive issues for a day or two afterward, even if your gallbladder appears to be working properly. I felt odd the rest of the day after the scan, not exactly painful, not exactly nauseated, but “off” and restless and uncomfortable. That evening, I had a mild attack with my usual epigastric and upper back cramping feeling and restlessness. That was the first time I really thought maybe my symptoms were gallbladder and not just gas.

I reported my mild attack to my gastroenterologist, and a couple days later she called back with my results. My EF was 79%, which is considered normal (but is borderline hyperkinetic; many doctors are not current on the literature and/or don’t believe that biliary hyperkinesia is a real thing). But in particular because the scan and its after effects replicated my symptoms, she recommended surgery and referred me to a surgeon.

Is surgery the only option?

At this point I was getting super stressed out. It seemed like all signs were pointing to surgery for this thing that I had thought was a non-issue and almost didn’t bother mentioning to my doctor. It seemed very drastic to remove an organ from my body when it hardly ever caused problems, and the casual way that doctors seemed to just automatically jump to surgery really bothered me. I know it is a routine surgery (more than 1 million cholecystectomy surgeries are done in the US every year), but it’s not routine for the individual having the surgery!

I started compulsively reading papers about gallbladder issues, pros and cons of surgery, alternatives to surgery, etc. I joined online communities on Reddit and Facebook to learn more about whether surgery was really the only option, what to expect if I did go ahead of surgery, etc. There is a ton of interesting and useful information out there, but the social media communities also tend to self-select for people who have more complications: people who get better tend not to stick around. So although I learned a lot I also did not help my anxiety about surgery.

The general medical consensus seems to be that since you don’t really need your gallbladder to live, removal is the best treatment option if you have symptoms. Once your body starts producing stones, it’s likely to keep doing so until you have an emergency, so it’s better to do the surgery electively than risk a necrotic gallbladder or pancreatitis and emergency surgery. There are treatments that can help to dissolve stones if they are small and non-calcified, but the impression I got is that those treatments are still usually just delaying the inevitable.

There’s also a lot of conflicting information out there about the long term effects of removal. Some sources will say that you can basically go back to normal and eat whatever you want immediately, others say that you likely will end up having to make long term changes to your diet (but because those changes tend to be toward healthier eating anyway apparently it’s all fine?). Some people suffer from long term effects such as pain, diarrhea, reflux, gas, etc. collectively called “post-cholecystectomy syndrome” but it is unclear how many of those cases are directly related to the surgery and how many are due to other issues.

A rant about medical imaging

I was wracked with indecision and decided I needed more information, so I set about trying to ask the radiologist’s office to provide me with the actual imaging and radiology reports from my ultrasound and HIDA scan so I could see for myself. (I had not yet done the upper GI x-ray because, frustratingly, the gastroenterology office referred me to a place that doesn’t do that particular imaging. We had to go back and forth several times, with them asking me why I hadn’t done the x-rays yet, and me telling them that they needed to refer me to a place that actually does the imaging they were ordering.)

Of course, the radiology office’s website was broken and they had no patient portal. I called them several times and followed their phone tree to try to request my medical records, but just got a voicemail box that never responded. Finally, I just pretended that I was trying to make an appointment until I got to a real live person, who took my request and passed it along to their medical records people.

Medical imaging is amazing. The quality of the images and the fancy tools used to analyze them are just fascinating to me as a scientist who analyzes data and writes analysis tools for a living.

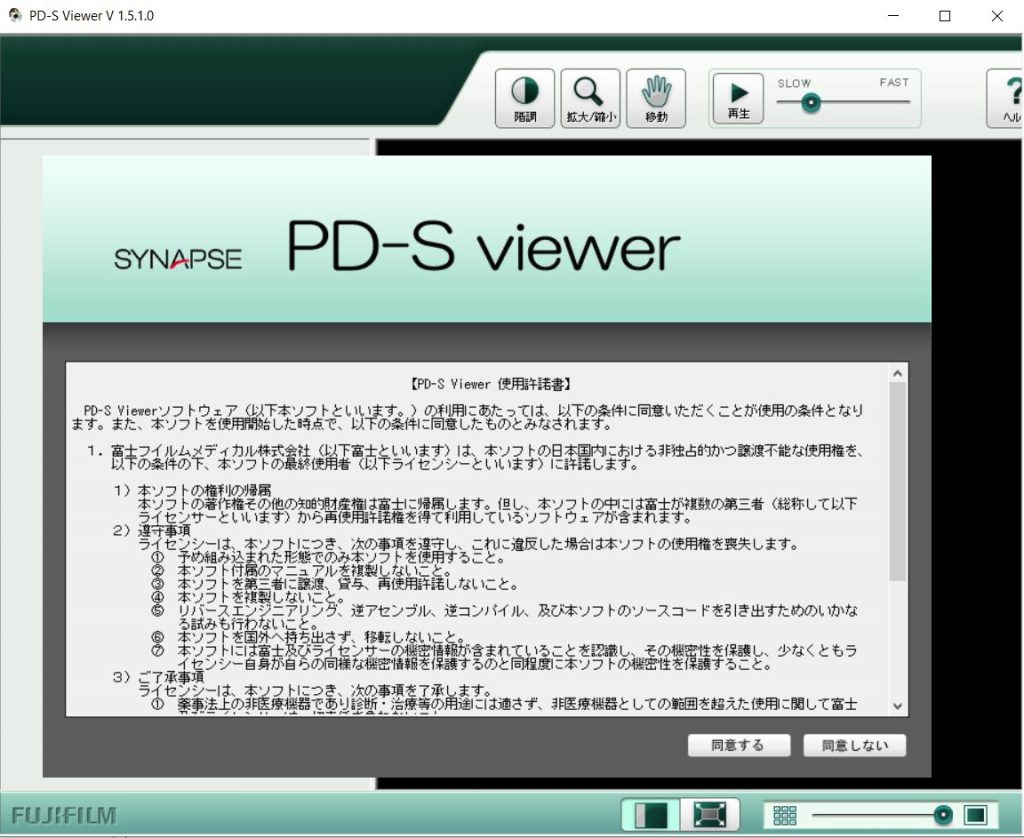

Given how advanced medical imaging technology is, you can understand why I was shocked that the only way to get a digital copy of the images was on a CD. I have not had a computer with a CD drive for probably 10 years. When they handed me the CD, it had a post-it note with instructions for how to access the files using a built-in image reader on the disk. Sounds great, right? If only I had a way to read the disk…

My wife took the CD to the library, where she was able to use one of their old computers with an optical drive to copy the files over to a USB drive. With the USB in hand, I booted it up and opened the image reader. Here’s what it looked like:

That’s right, the tool was in Japanese. Not to be deterred, I opened up Google translate on my phone to see if I could just struggle through the Japanese interface and see my darn images.

But not only was the tool in Japanese, it also could not find the images. Navigating through the disk directories on my computer, there were files there, but nothing recognizable as an image.

I almost gave up, but in my frustration I posted about this on Facebook and a friend of mine came to the rescue. She suggested that I try a free medical image reader called ONIS. Amazingly, it worked and I was able to export my images as JPGs!

It really boggles my mind that this is how medical images are shared with people. I am a scientist and I figure out how to read and work with weird data formats for a living, and I was barely able to access the images. They’re shared on obsolete physical media, with a viewer that is not in English and also does not actually work to view the images. It’s just unbelievable.

What the images showed

I was shocked when I looked at the ultrasound report and the associated images. When my GP said that I have “gallstones” I figured we were talking grains of sand. Maybe gravel-sized. I do not have “gallstones,” I have GALLSTONE. Specifically, to quote the radiology report that came with the ultrasound images, I have “a dominant 3.3 cm calcified stone within the fundus of the gallbladder”.

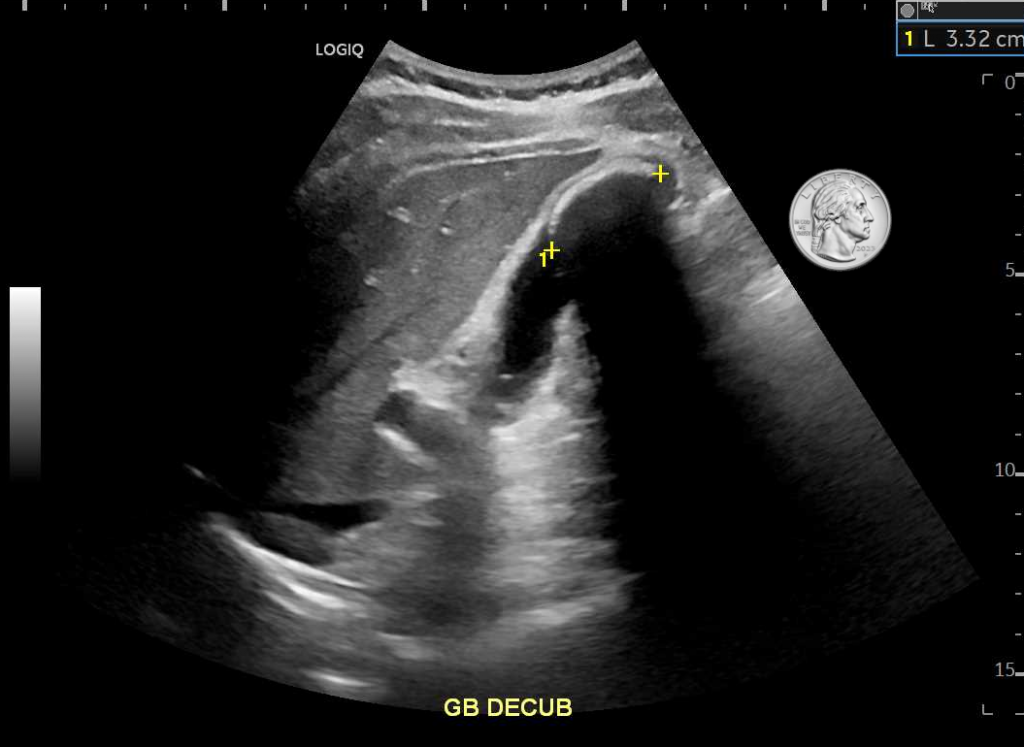

Recall that a normal gallbladder is only about 4 cm wide and 10 cm long. That means I have a stone that is taking up a significant portion of the volume of my gallbladder. Just take a look at this image:

I was really struggling to wrap my head around how big a 3.3 cm stone really is, so I put together another picture, comparing a 3.3 cm circle to other familiar objects:

(As an aside, the ultrasound was a full abdominal ultrasound, so they also checked out my other organs. It’s kind of weird and neat to have pictures of my liver, kidneys, pancreas, spleen, and aorta.)

The HIDA scan results were also interesting. As I mentioned before, despite the apparently enormous gallstone, my EF was 79%. You can see in this first image how they calculated that number:

Here are the individual HIDA scan images. They form a time lapse showing the tracer moving from my gallbladder into the duodenum:

The Upper GI X-Ray

I’ll just briefly talk about this because it didn’t show anything remarkable. This test’s full name is Upper GI X-ray series with air contrast and upper bowel follow-through. It has a few parts. First, you drink a barium slurry while standing up and they take x-rays, next, they lay you down and have you drink to see if your esophagus works ok without the help of gravity. (Barium is opaque to x-rays, so it lets them take pictures of soft parts of your body like your digestive system that normally wouldn’t show up in an x-ray.) Next, you swallow a mouthful of what the x-ray tech described as “super pop-rocks” (based on the taste, I think it was citric acid and baking soda). This makes bubbles in your stomach (they tell you to try not to burp) which, combined with some barium slurry in your stomach, makes it easier to see how your stomach walls are doing.

Next you have to drink a really large amount of the barium stuff. It’s thick and weird but not too bad. Then they take pictures every 15 minutes for an hour or two and watch the barium move from your stomach through your small intestine. Finally, when it has gone all the way through your small intestine, they do some final images. This last part was extra weird because the radiologist comes out with a big plastic paddle with an inflatable rubber ball on the end, and he firmly pokes and prods your abdomen while more x rays are taken. (They use the paddle so that his hands don’t have to be in the picture.)

I don’t have the images from this test yet (they’re mailing me another CD…) but they were very cool to see on the screen. Like the ultrasound, it’s just kind of neat to have pictures of my own guts and bones. The radiology report said that everything looked ok, except that my big fat gallstone showed up on the x-rays (more evidence that it is calcified). So as far as we can tell, there’s nothing else going on other than the gallbladder issues.

Another small rant

I also want to mention the astonishing lack of communication between medical offices, and with patients. I am 99% sure that my GP didn’t tell me I had an enormous gallstone because he didn’t know. My suspicion is that the radiology office just sent the written report, which was read by someone other than my GP at his office, and he was just told the diagnosis: cholelithiasis (gallstones), which he relayed to me.

When I went to the gastroenterologist, they did not have the ultrasound results. When I went to the surgeon for consultation, he did not have any of the imaging results. Each time I had to verbally describe the situation to bring them up to speed.

I also have not yet been able to be seen by my gastroenterologist’s office yet since my initial visit where they ordered the HIDA scan. First the follow up was delayed because they kept ordering the x-rays from a place that doesn’t do them. Then the follow up appointment was canceled and rescheduled twice because they kept making appointments for me to speak with someone who is not on my insurance. This last time they canceled, they tried to book me an appointment in June and I had to flat out tell them (remember, their office is the one that referred me to surgery) that I am having surgery on May 10, and that I want to talk to a gastroenterologist before I have an organ removed from my body. They are squeezing me in to see the actual doctor on May 6.

More Symptoms

Since the HIDA scan and discovering the magnitude of my gallstone, I’ve been hyper-aware of every little ache and pain and discomfort in my body. I am not sure how much is just psychosomatic and how much might be related to either the HIDA scan irritating my gallbladder, or just my condition getting worse, but I have started to notice a more persistent discomfort in the upper right quadrant.

Earlier this month we took a road trip from Arizona to Texas to see the eclipse (which was spectacular). I normally don’t have to watch my fat intake but I also don’t normally eat fast food for every meal. A couple days into the trip I had my first real attack in over a year (if you don’t count the HIDA scan). In a hotel room, trying not to wake the kids, unable to leave them alone in the room to pace around the hotel: not my preferred place to have a gallbladder attack.

I had another attack shortly after getting back from that trip, and have generally been having more symptoms since. There’s a persistent ache or feeling of pressure where my gallbladder is. Sometimes it feels more like a bruise, combined with a burning sensation like from an overworked muscle (ok, probably literally is an overused muscle). I’ve also started to feel faint discomfort in the gallbladder area if I take a really deep breath and hold it, or stretch my arms over my head.

Surgery is the right choice

All of this might sound unpleasant, and it is, but it’s also reassuring in its own way. It is a reminder that I am having surgery for a reason. Even though I usually can eat whatever I want, recent experience shows that is not always the case anymore.

I also was reminded over Christmas, as I shared the gallbladder saga so far with family, that my grandfather died of biliary cancer (I knew he had liver failure, but had not remembered that his cancer started in the biliary system.) Given that history and the fact that gallstones larger than 3 cm in particular are associated with chronic inflammation and an increased cancer risk, it makes sense to get the surgery even if I was not having other symptoms.

I still am very apprehensive about what life will be like after the surgery. I love eating fatty foods (who doesn’t) and I would hate to trade a normal life with occasional discomfort for constant bathroom issues and nothing but bland food. But I try to keep telling myself that it’s the right choice, and that very likely I’ll be back to normal, minus the cancer risk and occasional attacks.

Conclusion

So, apologies for the very long post. I hope if you’re someone who knows me that this was a useful update about what’s been going on. And if you are someone who doesn’t know me I hope this was a useful distillation of various information about gallbladder issues and treatment. I also hope this illustrates a few lessons that I have learned:

- If you have a health issue, tell your doctor. Worst case it’s nothing, but you might find out that you have an enormous gallstone!

- Ask for your images any time you have medical imaging (but be prepared for the CD and the weird image format)

- Advocate for yourself and don’t assume any of your doctors will communicate with each other

I plan to write a follow up to this post some time after surgery, once I have the energy. I’m told recovery is usually 1-2 weeks, but many people feel fine within just a few days. So we will just have to see. Here’s hoping it all goes smoothly.

Ryan, I’m your dad’s cousin. So sorry you have been dealing with this. However, I must say thank you for the information and thorough education on all things gallstone related. I was totally into every word of it. I hope I never need to know it for myself, sounds miserable—but I like to have baseline knowledge for all my many family members just in case. You never know.

Good luck with your surgery. God love the internet, social media, blogs, and old library computers with disc drives.

Hello Ryan,

Thank you for this informative perspective on gallstones. I also, unfortunately am facing the same difficult decision. The clarity you have provided is remarkable and much appreciated. I feel better equipped for what’s ahead and hoping for the best outcome. Best of luck to you and anyone dealing with dreadful gallstones.

I have been having similar problems and my doctor suggested a gallbladder issue. Your post is further evidence to me with your great (but sadly familiar) description of the sort of pain you experienced in an attack. I spoke to a friend earlier today and it was not until he collapsed and rushed to hospital than he was diagnosed so something that perhaps need a little more awareness. Thanks for sharing your experience – I have found it very useful.