Last night my wife and I went to see Ira Glass in his stage show “Reinventing Radio”. For those who aren’t familiar with him, Ira Glass is the host of the radio show This American Life, which is one of the best shows on radio (I’d say its only real competition for the top spot is RadioLab). It is great because it tells great stories, and the stage show that we saw was basically Ira Glass talking about how they put together a radio show that is interesting, touching, and nearly impossible to stop listening to. Many of the points that he made apply to written storytelling too, so I though I’d list a few that stood out.

1. Dark and serious is not the same as realistic

Glass spent some time discussing what makes This American Life different from typical broadcast journalism, and to do so he played a clip from CNN, reporting on the war in Afghanistan. It had everything you would expect: Very Serious reporters, epic music in the background, and everything about it just screamed “this is very important and serious”. Glass pointed out that this is all a stylistic choice. That broadcast journalism has sort of built up this standard tone that focuses on the serious, but in doing so they exclude humor and amusement and friendship and a wide swath of the human experience. In short, Glass said, the tone that broadcast journalism has self-imposed excludes “everything that makes life worth living.”

As a contrast with the CNN clip, glass played a clip from when their reporter was on the aircraft carrier that was running sorties into Afghanistan. They were interviewing a young soldier whose job 12 hours a day was to fill the vending machines on the aircraft carrier. It was a cute little moment of humor in an otherwise really serious setting, and made for very interesting radio.

Anyone who pay attention to popular culture is aware of the recent trend toward “grittiness” and gray characters and moral ambiguity in movies and books. There’s a whole subgenre of fantasy called “grimdark” now because of this trend. I think there is the assumption that by going “gritty”, the stories told are more realistic. But Ira Glass makes the really important point that this isn’t so, that life is a complicated mix of serious and funny, nasty and wonderful. If you only focus on the grimdark side of things, you’re not giving a realistic picture of life.

2. All stories ask questions

Glass also talked about the importance of plot. He quoted someone (whose name I unfortunately forget) who said that all stories are basically detective stories: they get the reader/viewer/listener to ask questions, and the desire the find the answer to those questions are what make you turn the page, or sit in the car with the radio for just another minute. Glass said that even just laying down the bare bones of the plot “this happened, and then this happened…”, if done right, gets the reader asking the question “Then what happened?” and that’s enough to keep people hooked. He also pointed out that this happens on all different scales in a story. There’s the big questions that stretch across the whole story arc, but there are also small questions that resolve themselves in moments. His example was “a figure stood in the doorway”. You’re immediately wondering whether this new arrival is a friend or foe to the protagonist. A few lines of dialogue, and you know the answer to that question and there is a small feeling of resolution. A great climax to a story is when a single event resolves lots of different outstanding questions.

On a related note, one thing that came up in the Q&A was that someone asked him about the pauses in the radio show and if they are deliberate. And the answer is yes, of course they are. Glass joked about how this person’s favorite part of the show was when he just shut up and let her think, but what clicked in my brain is that the short pauses that they intersperse in the radio show are actually examples of narrative tension on the sentence level. Just a short break in the flow of words lets the listener (a) think about what was just said, and (b) build suspense for what is about to be said. The exact same principle can be applied in writing on multiple scales by varying the pacing of a scene or a chapter, or even by the placement of words and punctuation in a single sentence.

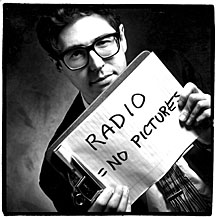

3. Sometimes “seeing” more lessens the impact

Glass began and ended the show by discussing the intimacy of radio. He made the point that, for some of their stories, if they had been filmed there would be so many visual details that distract from the point of the story that it would be almost impossible to have the same effect. Viewers would see the people and the setting and subconsciously (or consciously) think “that person isn’t like me” and therefore might not empathize quite as much with the people being interviewed. They would automatically judge the person onscreen and in doing so, distance themselves from the actual story. For example he talked about a very detailed piece they did on an inner-city school in Chicago, and he said that one of the main goals was for listeners to get beyond their preconceptions and, when they hear the story of the kids whose lives are full of gangs and shootings, realize: “That could be me” and “I would do the same thing in their shoes”.

I think the idea that the lack of visuals in radio can have this power to make a story more intimate can carry over to written stories and fiction. Of course, when writing you need to include some visual details, but choosing those details judiciously and allowing the reader to fill in the rest is an important part of getting the reader to buy in to the story.

4. What’s the point?

This is another aspect of the need to relate to the characters in a story. Glass pointed out that, when you’re telling a story to a friend, you don’t generally just stop, you wrap it up with a statement that just comes right out and says “this is the point of the story.” One example he gave was a really captivating piece they did about a girl in New Zealand who has been bitten by a shark. She was taken to the doctor and stitched up and the doctor told her parents that she would be in a lot of pain but not to worry about it, she’ll get better. But overnight, she gets worse and worse (it turned out the bite had punctured her intestine and she was getting peritonitis and close to death). She tries to convince her parents that things are really bad, but they don’t believe her, thinking of the doctor’s warning that it would be painful, but not to worry.

Gripping story right? You want to know how it is resolved. But what Glass said was that what really makes the story resonate is that it is the most extreme example of something everyone experiences: being a kid and trying to convince your parents of something that you know to be true, and they don’t believe you. Now for most of us, this experience is more about monsters under the bed or the importance of high school drama rather than a life-threatening shark bite. But Glass’s point was that every story that is any good has a key point that links it to the listener’s own personal experience, and that getting the people he interviews to focus in on this key point is a big part of conducting an effective interview. He said that basically the goal is to get someone to come right out and say what the point of the story is.

This can be tricky to do in fiction, but I think the idea is still valid. Even if you don’t want your characters to stand up and tell the reader “this is why you should care about this story”, it makes sense for the author to be keenly aware of this central idea that the reader can relate to.

5. It’s a volume game

Multiple times, Glass mentioned that “it’s a volume game”, meaning that to get the good stuff, you have to work through and discard a lot of junk. For the stories included in the show, he said that more than half of the stories that they start never air because they aren’t good enough. And for stories that do air, most of the interviews never air.

During the Q&A at the end, someone asked how Glass can do radio so much and stay “authentic”, and he responded by saying that it takes a lot of practice to be good enough to be yourself. This segued into something that I had heard him say before in the excellent video clip below. Basically, the only way to become good enough is to do a large body of work: