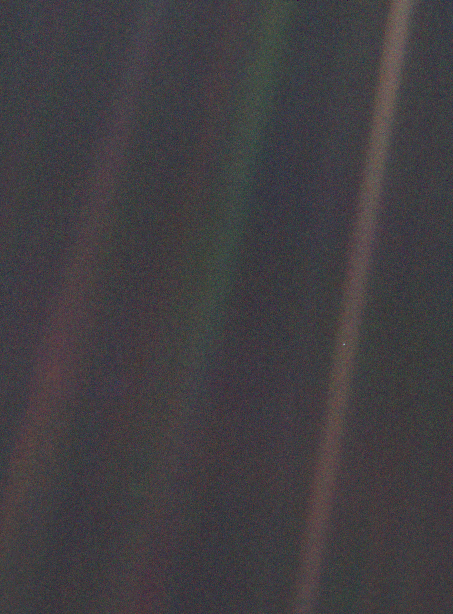

Look again at that dot. That’s here. That’s home. That’s us. On it everyone you love, everyone you know, everyone you ever heard of, every human being who ever was, lived out their lives. The aggregate of our joy and suffering, thousands of confident religions, ideologies, and economic doctrines, every hunter and forager, every hero and coward, every creator and destroyer of civilization, every king and peasant, every young couple in love, every mother and father, hopeful child, inventor and explorer, every teacher of morals, every corrupt politician, every “superstar,” every “supreme leader,” every saint and sinner in the history of our species lived there–on a mote of dust suspended in a sunbeam.

The Earth is a very small stage in a vast cosmic arena. Think of the rivers of blood spilled by all those generals and emperors so that, in glory and triumph, they could become the momentary masters of a fraction of a dot. Think of the endless cruelties visited by the inhabitants of one corner of this pixel on the scarcely distinguishable inhabitants of some other corner, how frequent their misunderstandings, how eager they are to kill one another, how fervent their hatreds.

Our posturings, our imagined self-importance, the delusion that we have some privileged position in the Universe, are challenged by this point of pale light. Our planet is a lonely speck in the great enveloping cosmic dark. In our obscurity, in all this vastness, there is no hint that help will come from elsewhere to save us from ourselves.

The Earth is the only world known so far to harbor life. There is nowhere else, at least in the near future, to which our species could migrate. Visit, yes. Settle, not yet. Like it or not, for the moment the Earth is where we make our stand.

It has been said that astronomy is a humbling and character-building experience. There is perhaps no better demonstration of the folly of human conceits than this distant image of our tiny world. To me, it underscores our responsibility to deal more kindly with one another, and to preserve and cherish the pale blue dot, the only home we’ve ever known.

– Carl Sagan, Pale Blue Dot, 1994

Month: January 2017

We’re back at the hospital again. Yesterday we came in because Erin was having some contractions that felt different from the normal Braxton-Hicks that are expected at 35 weeks. They sent us home, telling her to relax and that these might go away or they might persist for another month. We were instructed to come back if they got “longer, stronger, closer together.” Sure enough, they intensified overnight, keeping both of us awake and miserable. So we’re back at the hospital again, first thing in the morning. We are fully expecting to be turned away again. I didn’t bother to pack a change of clothes or food in our hospital bag because this is surely another false alarm.

Our nurse today is younger and nicer than the one we had yesterday. She checks and Erin is 3 cm dilated. We are informed that the baby is coming today.

We try to digest this information as Erin is whisked to a delivery room. This was not the plan. It’s 5 weeks too early. We are told that most babies born at 35 weeks do fine. I was born at about 35 weeks and I was fine. But we’re still terrified. What if this is happening because something is wrong? What if he can’t breathe because he’s too early? At the same time, it’s thrilling. We’ve been waiting and preparing for this and now it’s finally happening! We get to meet our son. Today!

It’s early afternoon and the delivery room is in chaos. Erin is standing beside the bed, holding both my hands, doubled over with the pain of a contraction. The nurses are frantically changing the mattress on her bed, because somehow it had the wrong type of mattress and she’s about to get an epidural so they need to change it before she can’t stand. The anesthesiologist has wheeled his cart into the delivery room and is complaining about how they’ve moved everything compared to how it used to be in the old rooms.

The mattress is finally changed, Erin is instructed to sit just so, and then during another contraction the doctor inserts the epidural and starts the drip of pain killer. Half an hour later things have changed dramatically. The pain has faded, the anesthesiologist has left, and the nurses leave too. For the next few hours, Erin rests.

Evening, and the room is crowded again because the baby is about to make his appearance. The doctor is all suited up, a team of nurses from the special care nursery is standing by along with the regular nurses to check out our preemie.

One more push and the baby is out, he is lifted up and placed on Erin’s chest, and we are both massively relieved when he starts to cry. It’s not super strong or loud, but it’s a cry. The next little while is a blur of activity and emotion. At some point the doctor asks if I am ready to cut the cord. I am handed some surgical scissors and shown where to cut. I had been told the cord would be tougher than you think, so it is instead softer than I expected.

The doctor asks if we want to see the placenta. We say no, but she doesn’t hear us and shows us anyway. It’s a big bloody bag made of surprisingly large veins. They take it off to the lab to be tested (standard for preemies) and ask if we want it back. No, thank you, we do not.

They weigh the baby (our son!) and he is a respectable 5 lbs 11oz. Not bad! He is breathing, he’s a healthy weight, his temperature is good. We’re feeling relieved. He’s going to be ok. The final hurdle is getting him to eat. Erin tries for a while but he is too exhausted and doesn’t nurse. The nurses prick his heel and check his blood sugar. It’s too low for them to get a good reading. We’re going to NICU.

We are in NICU and my son (!) is sucking on my gloved finger. The nurses told me to dip it in sugar water and let him suck it as a distraction/pain relief while they try to put an IV in his tiny veins. They are having trouble. They have tried both hands with no luck. They’re back to the first hand, using a bright light to shine through his hand and find the vein. They finally give up and tell me that he will need to get an IV in the umbilical vein. Erin comes down at some point in a wheelchair to see the baby, but there’s not much room and they need room to work. She heads upstairs to rest.

The doctor comes over. I have to stand back because this is a sterile procedure. The doctor seems very disorganized, not knowing where things are, and the kit of supplies he is using is missing things. Assorted items are cast aside on the ground. He complains about how short the umbilical stump is and admonishes our ObGyn for leaving it so short. (I feel an irrational pang of guilt, since I cut the cord) But in the end the catheter is inserted, and baby gets the sugar he needs. After the procedure, the nurse apologizes for the doctor: he is very experienced but new to Flagstaff and still learning how things are done here. It’s been a few hours since the birth. It’s after midnight and I’m exhausted and there’s nothing more to do. I now have to leave my baby in a plastic box, connected to wires that read his pulse, his breathing, and his blood oxygen levels, along with the IV that is feeding him. I go upstairs and try to rest.

It’s been a couple of days, and after all of that, we are home and our baby is still at the hospital. This feels wrong on a visceral level. The dogs are happy to see us home, the house is just the same as it has always been, but it suddenly feels very lonely.

We are grateful for the flood of love and support that we’re getting on Facebook because we don’t have any local family and our baby is in the NICU instead of home in our arms.

We decide on the name Shane. Middle name is mom’s last name, last name matches mine. It feels good to finally settle on something after months of thinking about it, but it’s also very strange. Naming a human being is hard!

Christmas eve day, and we’re just about to leave the NICU to go home for lunch. Our jackets are already on when Shane wakes up and opens his eyes. Other than right after the birth, he’s had his eyes closed most of the time. We get our first chance to really look him in the eye. He’s beautiful, and it is heartbreaking to leave him.

It’s Christmas eve. Shane has been put on a “bili blanket” to treat newborn jaundice, a common problem. The glowing blue blanket makes it look like he is acquiring superpowers. A winter storm is blowing in, promising everyone in Flagstaff a white Christmas, and making it extra inconvenient for us to come in to see our baby. But we do of course. We complain about the storm but it’s also sort of nice to have a concrete way to demonstrate our love. We will not be prevented from visiting our baby by a little snow!

We have been moved to a roomier cubicle, right by the window, and so we spend Christmas eve in the dark, warm NICU with a view of colorful Christmas lights on the trees and snow coming down hard. Inside, we have the dim light of the ever-present monitors, showing us our baby’s vital stats. We sit there as a family and I read aloud from The Slow Regard of Silent Things and even though we’d rather be at home, everything seems right with the world.

The days begin to blur into one another. His IV gets swapped out for a feeding tube in his nose, which means he’s also allowed to wear clothes now, which is seriously adorable. His jaundice clears up and the light blanket is removed. He gets moved to a smaller crib, and back to our original, more cramped cubicle. Our lives are now scheduled around the feeding times and meeting times set by the hospital. Every day, we get in before 8 so that baby can eat at 8 and one of us can get an update from the NICU team. The euphoria of the first few days starts to wear off. We thought he would only be in the hospital for a few days but here we are, still at the hospital. I start to worry about health insurance, especially since it looks like his hospital stay will cross over into the new year, making us pay twice.

Shane’s oxygen levels also start to fluctuate. When he goes into a deep sleep they drift down, flirting with the 85% level which sets off the oxygen alarms. Sitting with our baby switches from being relaxing to nerve-wracking. Instead of looking at his peaceful face, my eyes are glued to that oxygen number, willing it to stay up.

One morning we are told that he may need to go on oxygen, which is a huge emotional blow. The number one thing I was worried about with a preemie was that he would have breathing trouble, and I thought we were past that once he was born and cried and breathed well immediately. That same morning, he does his best breast feeding yet, 19 minutes, but the nurse assumes he isn’t going to get a full feeding and pumps him full of a full meal with his feeding tube as well. She also refuses to weigh him before and after the breastfeeding to see how much milk he got. We are annoyed and distraught.

At rounds, we get a little more information about oxygen. Apparently babies sometimes need oxygen once they start having to digest larger meals because the digestive system uses more oxygen than they needed before, This makes absolutely no sense to me: why would the body prioritize digestion over proper blood oxygen levels? If having a full stomach causes his oxygen to dip, why the heck did the nurse just force feed him a second meal on top of the one he was already eating? But the nurses assure us that oxygen isn’t a big deal, that it’s very common at our elevation, and that if necessary he can come home on oxygen. Despite that, we’re quite upset. He’s supposed to be getting better. Requiring oxygen is not a sign of getting better.

It’s a few days later and we’re getting used to the oxygen. I am giving him a bottle, tilting it to give him a break every few sucks as we’ve been instructed, when he chokes. After a weak cough, he stops breathing. His oxygen levels drop and the alarm starts going off. Unlike other times that this has happened, his levels stay low. I am holding him in my arms and watching him turn blue and there is nothing I can do. Erin rushes to get a nurse, who turns up his oxygen and sits him up. He finally takes a breath and recovers. We give him the rest of his feeding through the tube and then head home for lunch.

I manage to keep it together until we are home, and then break down. I’ve never felt more scared and helpless than I did watching him go limp and change colors. I still desperately want him to come home, but now I’m also terrified. What if that had happened at home with no nurses nearby and no oxygen? Maybe I don’t want him to come home after all. I stay at home that afternoon and try to emotionally recover.

The next few days are up and down. Sometimes he does really well, other times he falls asleep after hardly eating anything. It’s a very confusing mix of emotions to feel all the love of having a new baby but also being angry at him for refusing to eat day after day (even though we know it’s not his fault). Sometimes the frustration is so strong I can barely handle sitting there and watching him ignore the milk he is being offered. Nurses try to make it better by joking “Get used to it, this is just a sample of how frustrating being a parent is.” But I hate it when they say that. This isn’t a behavior issue with an older kid. I actually feel pretty confident in my ability to handle things like that. This is a baby failing to fulfill biological necessities. This is brainstem-level behavior and he isn’t doing it and it is driving me crazy. I start to get paranoid that there is something developmentally wrong with him (and I am eternally grateful for the nurses and other support people who recognize this concern and repeatedly reassure me).

We are sitting, talking to the NICU social worker, whose job seems to be to ensure that the parents are ok and that when baby goes home the family will have a safe and supportive environment. Just as I am telling her about how my main complaint about the otherwise wonderful NICU care is that sometimes we are told something that, without context, seems pretty alarming (for example, the oxygen thing), a nurse comes over and listens to Shane’s heart and says that she hears a murmur. We get to panic about that for a little while until it is explained that they check for heart murmurs by default whenever a baby has to go on oxygen, and that it sounds minor but needs to be followed up with an ultrasound.

The next day, a giant futuristic-looking ultrasound machine appears, and we watch as they look at his heart and take lots of snapshots and recordings. Of course the tech can’t tell us anything, so it’s another day before we know the results: Shane has an ASD (atrial septal defect) and a PDA (patent ductus arteriosus). PDAs are present in all babies in-utero and tend to close on their own in most cases. ASDs are less common, but we are told his is small and also likely to close on its own. We are told they tend to get loudest right before they close which may be why it wasn’t detected before. If it doesn’t close on its own, it should be treatable without surgery.

I swing between being pretty upset about it and being philosophical about it: these defects were only detected because he was in the NICU and on oxygen. There’s a good chance that he could have grown up with them and nobody would have known. Many people don’t learn they have an ASD until they are middle aged and have a mini-stroke. It’s better to catch these things early so they can be monitored and treated.

But still, the last thing you want to hear is that your baby has a problem with his heart. One more apparent setback. One more complicated emotion to add to the mix.

Suddenly he’s doing better. He is weaned off of oxygen overnight on the 7th, and he eats reliably for two days in a row, is actually acting hungry when he wakes up, and suddenly the nurses are talking about going home! To go home he has to pass the “carseat challenge” which involves sitting in his car seat for at least 90 minutes with no oxygen issues. He passes with no problems. We are told to go home and get some things, we will “room in” with him tonight and if all goes well, he can go home tomorrow.

The “rooming in” room is like a hospital version of a hotel room. Big, decent bed, private bathroom, but just down the hall from the NICU in case anything bad happens. We wheel him back in his crib and for the first time we have an (almost) cordless baby. The leads for the ECG and breathing monitors are still attached, but they just get tucked into his clothes. We can pick him up without having to worry about unplugging something from the wall! We have privacy and space to move around with our baby for the first time! One of the things that we notice most is how quiet it is. Three weeks in the special care nursery and we had stopped noticing the constant background hum of monitors and babies fussing and nurses and parents talking.

We settle in for our first night with our baby (still punctuated by nurses coming by to check him). We don’t sleep much, but it’s great because it means we’re done with the NICU.

And then we are home! After waiting so long it hardly seems real, but there’s our little boy in his own bassinet in our own bedroom. No wires attached, no oxygen tubes or feeding tubes. No monitors giving us a heart attack every few minutes. Just our baby. In our house!

We introduce him to the dogs. Renly is quietly excited, wagging and licking his face a few times. Pippin is oblivious, and responds the way he always does when we’re paying attention to him: by rolling over and showing us his tummy.

The first night is rough. When he is stirring and making noises, we worry that they’re noises of distress. When he is silent, we worry that he has stopped breathing. We don’t get much sleep. We realize we need some dim lights in the nursery. We realize we need a laundry hamper handy near the changing table.

It is amazing how relaxed life seems now that we don’t need to rush back and forth to the hospital multiple times a day.

Over the next couple weeks, we take Shane to his first pediatrician appointments, we get newborn pictures taken, we give him his first bath at home and his first infant massage. He gets to meet some friends, and my parents get to see him at home instead of at the hospital, trailing wires.

It’s the middle of the night. Nobody is sleeping. Why didn’t anyone tell us about the noises? Crying would be one thing, because then it’s clear that something is wrong, and you get up and fix it, but he hardly ever cries. Instead he spends most of the night squirming, kicking, straining, grunting, gurgling. All while apparently remaining asleep. He sounds like a little tauntaun and it’s driving us crazy. Is it gas pain? Does he think that straining and grunting will help with hunger? If so, how do we teach him that, no, they don’t?

We look online and this seems to be the norm for newborns. Nobody has a good solution for it. I don’t know who the heck coined the phrase “sleeping like a baby” but it’s awfully misleading. I had assumed the sleep deprivation that people talk about was related to crying, not this weird grunting.

We understand now why all the warnings about SIDS are drilled into parents so forcefully, because it is awfully tempting to bring him into bed with us and let him sleep on our chests (the only position where he really seems to sleep quietly) while we sleep.

And now, as I write this, I have reluctantly started to ease myself back into work. I am extremely lucky that I’ve been able to take so much time off, but for some reason the world has not put itself on hold while I’ve been away and I need to get back. I find that my perspective has shifted. It’s awfully hard to care about esoteric questions about Mars when current events are so awful and I have a baby at home to take care of. Can’t I just be a stay-at-home Dad and snark about politics online for a living? No? And even though I’ve been off for a while, it feels like three weeks of my leave were stolen from me: I expected to spend all of my leave at home with my baby, not shuttling back and forth to the hospital, sitting in an uncomfortable chair in a cramped cubicle, unable to enjoy my time with my baby because he won’t eat and his oxygen keeps dipping too low and because I’m stressing about what health insurance plan to choose to cover the likely $100,000 hospital bill headed my way.

I guess the lesson in all of this is that life doesn’t go as planned, and to be flexible and grateful for what you have. Because at the end of all of this, the only thing that matters is that my family is home and happy. We know that despite everything, we’ve been very lucky. Lucky that he is healthy, lucky that we could take time off of work, lucky that we live close to the hospital, lucky that we have health insurance, lucky that we live in a time when Shane could get the treatment he needed. We are incredibly grateful for the many excellent nurses who took care of him (and us).

Now we get to enjoy our new life with him, watching him grow and change every day, and figure out this next chapter in our lives.